From

The Revolution of Rome by Alberto Pagano Benedetto:

The people of Papal Tunisia and Palestine found themselves in legalistic limbo as the dictates of the new Roman Constitution came into their lives. As their land was considered by the new Roman state to be Vatican property, they were not considered denizens of Rome proper, and were therefore unincluded in the extension of Roman citizenship to residents.

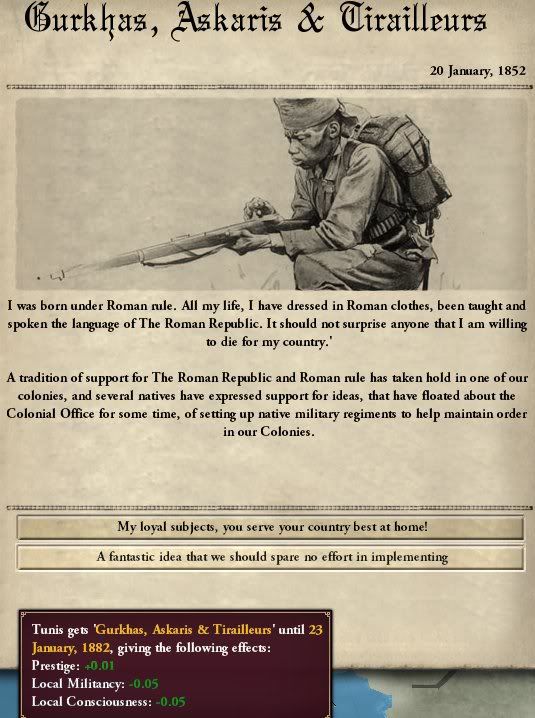

There were still ways to citizenship that extended to one's dependent family, most directly by enrolling in Roman civil service; the most accessible of such jobs were those involved in the military and so the immediate years following the Revolution of 1852 saw a dramatic increase in the number of non-Italian regiments fielded to secure the fledgling Republic. Until this, the Army was a swath of volunteers from across Italy eager to protect the first true modern Italian republic.

North of Rome, nationalistic sentiments fomented unrest and protests against Hapsburg rule. Hungarian leaders eventually coaxed the Austrian Emperor to grant generous privileges to the eastern nobility, and the newly-crowned Franz Joseph even adjusted his title to include that of Apostolic King of Hungary; the Hungarians were granted autonomous rights, the formation of their own parliament, and 30% of Imperial income. On March 19, 1852, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise was signed and the Hapsburg Imperium became known henceforth as the

Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie.

The Roman Republic was recognized immediately by the United States of America, leading to Great Britain's acceptance and the greater whole of Europe, but Austria and France refused to grant legitimacy to the Republican states and Italy had demanded the immediate cession of all land north of Rome since the beginning of the year. Roman attempts to spread influence within the weakened Italian state were deflected by French agents almost effortlessly, and relations between the three nations rapidly disintegrated.

The Republic drew further condemnation from the Catholic Mexican monarch, the latest Emperor to emerge from the tumult of the New World. The overseas threat carried no weight and was seen as a politically motivated act inspired by mere opposition to the United States, which had left the former Spanish colony in a shamble of native uprisings.

To defend against possible aggression from those with a mind to restore the temporal sphere of the Papacy, Rome began to assemble the People's Army to supplement the overstretched forces of the Church. Issued with the new

Zündnadelgewehr rifles from North Germany, the Republic was determined to make up for inferior numbers with surpassing tactics and weaponry.

The summer of 1852 saw the first test of Roman authority by one of the other powers; the Ottoman Empire had long insisted on a wider border than the Romans claimed divided Papal and Turkish Africa, and the tension peaked when, once again, a Roman citizen was arrested by Ottoman soldiers on Roman soil. The hawks of Rome called out for war, and their voices would drown out the doves.

Roman influence continued to spread to friendly nations - Spain was ready to throw support behind the Republic when France declared a hostile war to acquire more Spanish land. It was as though France were daring Rome to intervene, but Spain would remain on her own.

As the States settled into the new mode of operating and the various legislatures assembled throughout the land, a quiet hope took hold of Italia. For a great many citizens life had hardly changed, except that now they could live where they liked, build what they liked, worship and speak and blaspheme as they liked. But in no sense was any of this freedom

gained in the truest sense of that word - indeed such freedom of action is God granted, a part of free will and human nature. The real change was that there was no longer a punishment for exercising that freedom and action, and it made life a lighter burden for a nation.

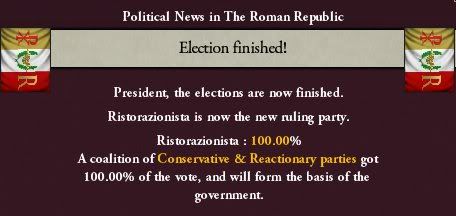

The end of the first election came on October 14, 1852, when millions of Roman citizens stepped out to cast their vote for the Consul of Rome. Each state would tally the votes, and the most voted candidate would receive the electoral votes of that State's senators (which, in the meantime, consisted of old State governors from the Papal days). Conservatives flocked into the Senate following the election, balancing legislative power with the many liberal and reactionary candidates elected.

Due to the curiosities of the Roman electoral system and the sheer number of available, Mondetat and Garibaldi would win immense numbers of individual votes but failed to win a single State Elector, as the voting majorities of various states all lined up to support various Conservative and Reactionary candidates. The extension of Universal suffrage turned out a massive blow to Liberal candidates, who were well-received by the Aristocracy but largely unknown to the formerly unlanded masses. Many were unsure of the democratic processes or the fall of the Papacy, and many sensing a religious duty to keep the Church in power voted overwhelmingly for clerical candidates. Cardinal Marcel Cicero, in particular, was notable in carrying 76% of the farmers' vote in Romagna.

Cardinal Cicero would go on to become First Consul of Rome with the majority of Electors, followed by Reactionary ex-soldier Gaspare Fornari and Conservative lawyer and shipwright Antonio Pirro who would fill out the rest of the Consulate. That the first Roman Constitution called for the Vatican to remain the highest judiciary in the land spoke to the influence of the pious and newly sovereign lower-class. Contrarily, in the South of Sicily and Naples, anticlerical sentiment ran high with great offense to the shocking defeat of Garibaldi and Mondetat. The Roman Constitution allowed for amendment, and already the liberals in Assembly pondered a way to secure the division of Church and State.

Tensions between Rome and her neighboring Kingdoms continued to escalate into the following year. Armies of Italy and Austria were maintained along . The new Republic would need to find allies or be ended in the cradle by her enemies. For now, the Pontific Army was stationed throughout the Legations and the people of Rome wondered if their newfound freedom would hold. If the Austrians made a move to restore the Pope to his holdings, everything could be lost.

It was in the early days of November that Pope Gregory stopped taking food; by the third week of the month, the Camerlengo addressed the citizens of Rome: The Pope, Holy Father of the Roman Church, Lord of the Vatican, the last king of the Papal States, had died. The nation fell into mourning and a summons was dispatched to Cardinal Secretary Gaisruck, who, along with fellow elector Cardinal Canalan, had fled the revolutionary Vatican for America. The Conclave that would decide the fate of Catholicism was soon to begin.

From the Journal of Cardinal Carlo Cristoforo G. GaisruckDecember 6, 1852

Pope Gregory has died.

I must return to Rome to cast my vote, if by some miracle there is time for me to return. Just as well I get going, Massachusetts is bitterly cold nowadays. How I miss the vineyards of Montalcino.

No need to take unnecessary risk, I'll be landing in Gaeta. My brothers shall greet me there. I just hope I make it in time to cast the veto.

The waterlogged script ends here. The wreckage of Carlo Gaisruck's transport would never be discovered, but the journal was recovered on the shores of Palermo in 1952, its protective case preserving much of the writing.

Poll

Poll

Author

Topic: Let's Play Victoria 2: Origin of Nations! - Dio e Popolo! (Ch. VII) (Read 62795 times)

Author

Topic: Let's Play Victoria 2: Origin of Nations! - Dio e Popolo! (Ch. VII) (Read 62795 times)